Hundreds of Alaskans died of the flu pandemic a century ago in Bristol Bay.

In the spring of 1919, the great Star Fleet of the Alaska Packers Association (commonly known as the “APA”) departed from San Francisco for Bristol Bay for another year canning salmon. When the ships arrived in mid May and anchored off their canneries, they found the waters largely free of ice--a sign that the winter had been relatively mild.What they found, upon going went ashore however, was anything but mild. The ship's crews encountered chaos, desperation and death brought about by the second wave of the Spanish Flu.

A TRAGIC TALE.

The Spanish Flu entered Alaska in 1918 following the steamship route from Seattle up through the Southeast Panhandle and into Prince William Sound. The first cases appeared sometime in the fall. It later came into Nome and the Seward Peninsula at freeze-up just after the last steamship departed. The rapid spread of the disease overwhelmed all efforts to control it. A person often died within days, if not hours, after infection.

The territory’s meager emergency funds were quickly exhausted, but Governor Thomas Riggs, hoping Congress would later reimburse the territory, authorized officials to continue to treat the sick, bury the dead and care for the growing number of children orphaned by the Flu.

Meet Dr. Linus French

In December of 1918, Governor Riggs also sent a message by dog team to warn Dr. Linus French, the doctor at the Government hospital at Dillingham, about the Flu. Dr. French immediately established quarantines for each of the communities in his vast service area that ranged from Ugashik on the Alaska Peninsula to Nondalton on Lake Iliamna and to Togiak in far western Alaska. Dr. French was hopeful that the quarantine and isolation would protect Bristol Bay. Sadly, Dr. French’s hopes were dashed when cases of the Flu began appearing in May of 1919. How the Flu arrived and where the first case occurred in Bristol Bay is unknown. However, given the insidious tenacity of the disease, the relative isolation of Bristol Bay was likely never an assurance of safety. As such, Dr. French and his staff of two nurses quickly became overwhelmed helping the afflicted in the nearby villages.

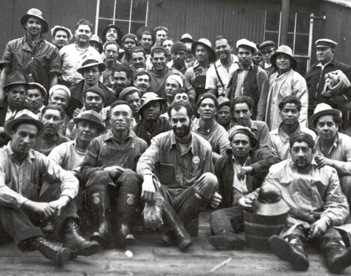

APA Cannery Crews were the first responders of their day.

The first responders in the Lake and Peninsula region were the canning companies. There were dozens of canneries scattered around Bristol Bay in 1919, most of them affiliated with the APA.

Canning salmon was then the industrial equivalent of today’s oil companies in Alaska. Because Bristol Bay was so remote, the companies had to build their own infrastructure and transport food, supplies and most of the personnel they needed to catch and process fish. That infrastructure included hospitals, doctors and nurses to attend to the medical needs of fishermen and cannery employees. At the time, the APA had small hospitals at Nushagak, Koggiung and Naknek.

Virtually every community was affected.

As soon as they came ashore, APA cannery crews began to help the plague infected villages. While the business at hand was preparing canneries for the short but intense fishing season, the APA, according to its own accounts, spared no expense to extend medical help to the afflicted, comfort the dying, build coffins, bury the dead and perhaps most critically, clothe, feed and house a multitude of orphans. Curiously, the Flu, an H1N1 variant, spared the young and reserved its cruel wrath for their parents.

Every community in the Lake and Peninsula borough, except Egegik, was affected by the Flu and some, like New Savonski, were devastated beyond recovery.

A pandemic compounded by a fishery collapse.

By the end of June, the Flu had run its course, but the disaster was not over--Bristol Bay's expected run of salmon in July did not come that year.

Overfishing to provide more food for the allied armies in World War I apparently decimated the 1919 brood stocks leading to the first major collapse of the Bristol Bay commercial fishery. The poor run was doubly disastrous for a Native population already diminished and weak. Starvation and more death ensued in some of the more remote villages.

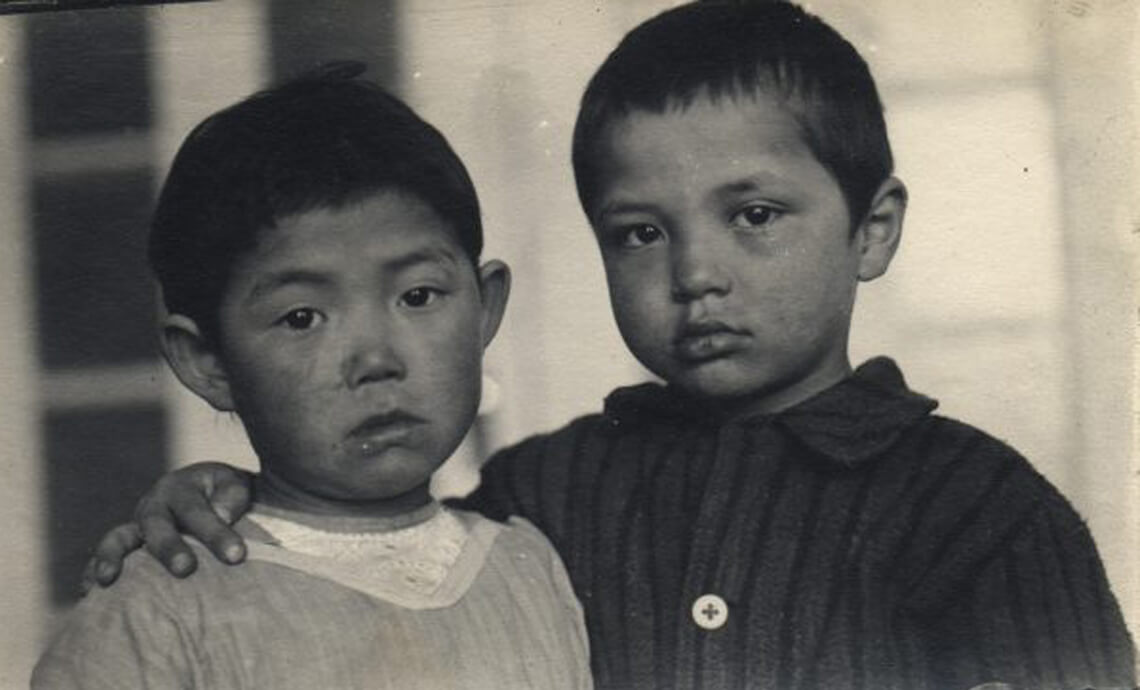

As the 1919 fishing season came to a close, the seasonal canneries could no longer house the orphans and most were delivered to the care of Dr. French at the Government hospital at Dillingham.

Having already faced what could only have been the greatest challenge of his medical career, Dr. French took on one more historic task before departing Bristol Bay--the establishment of an orphanage for 110 children who lost their parents to the pandemic. Many of those orphans came from villages within the Lake and Peninsula region.

A devastating toll that could have been much worse.

Historians estimate that some 40% of the adult population of Bristol Bay died from the Spanish Flu in 1919, but no one really knows. Unmarked mass graves all around Bristol Bay conceal the actual numbers. Many villages just disappeared, taking their stories with them.

What can safely be said, is that hundreds died and hundreds more would likely have followed, were it not for the dedication of a doctor and two nurses at a scrappy government hospital in Dillingham and the generosity and quick action of the salmon canning industry, in particular, the Alaska Packers Association.

"Know your local history. Regardless how long our time connected to Bristol Bay, we have all been shaped by its triumphs and tragedies and the generations that came before us."

Tim Troll

Executive Director of the Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust